The clade Pancrustacea includes both crustaceans and hexapods. So it makes sense that cicadas taste, writes Chris Alice Kratzer, a little like shrimp, albeit “somewhat nuttier and earthier.” This also means you should stay away from them if you’re allergic to shellfish. Evolution is nutty that way.

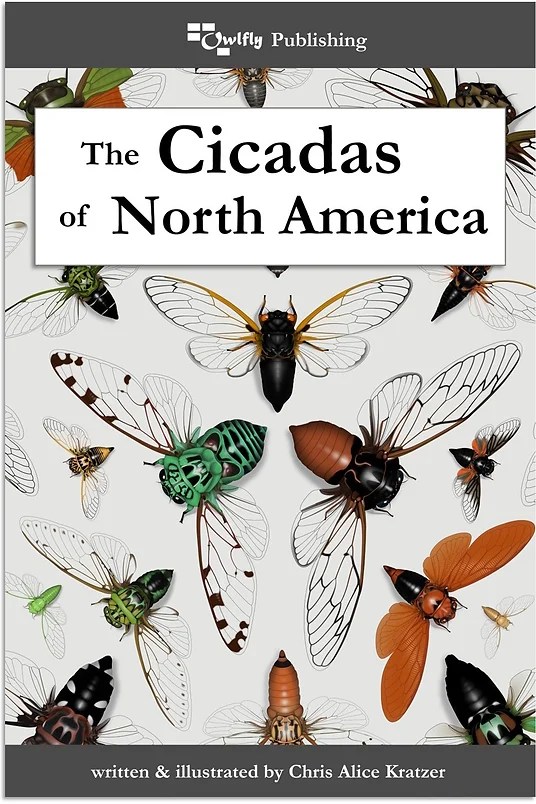

In her new guidebook The Cicadas of North America, Kratzer adventurously tackles 374 species in 53 genera, plus 33 regional color forms. 21 undescribed species are also noted; she thinks there are plenty more undescribed species out there.

374, by the way, is only a little over 10% of the world’s cicada species. Cicadas have done pretty well for themselves here on Planet Earth; their underground nymph stage seems to have helped protect them from the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event, which took out about 75% of the lifeforms on the planet over 66 million years ago. Dirt-world wonders, then.

Central America hosts the greatest number of cicada genera covered in this book, while California has the most cicada species. The Eastern U.S. makes up in terms of numbers of individuals, particularly when it comes to the periodic 17- and 13-year cicadas. The next brood of these Magicicada to watch out for, by the way, should start emerging in June. Brood 14 is named the Appalachian or Great(er) Eastern Brood; it has populations on Long Island and Cape Cod, or at least did the last time around.

The book’s front matter details evolution and taxonomy, anatomy, life cycle, ecology, human influences. This is really helpful. Here you can find such great details as the following. Cicadas feed on plant sap, which is mostly water, so they pee a lot: 300 times their own body weight every day. (Think really big aphid!) They also excrete a gluey substance to anchor their exoskeletons in place for the breakout from their exuviae, which explains why you can find exuviae upside-down on tree branches.

Each species gets a page-long treatment. Kratzer uses the same space-maximizing format of her earlier The Social Wasps of North America, which I consult regularly: each drawing is half one color form, half the other form; if you want to see the whole use a small mirror or just visualize in your head. (Talk about bilateral symmetry in lifeforms: these books are predicated on it!)

Unfortunately, many species are difficult, if not downright cryptic, to identify down to species. That’s the case with the Neotibicen dog day cicadas, the genus I’m most familiar with. The best way to distinguish them is by ear. Only the males “sing,” snapping their tymbals, making a sound which resonates in their mostly hollow abdomens. This being a book, however, it can’t link to sound recordings. (It was a notably quiet year for cicadas here in Brooklyn.)

This book is a positively heroic undertaking. It probably would have been impossible a generation ago, I mean in terms of finding an audience, but there are so many more community scientists/naturalists out there now hungering for details on the life around them.

Leave a reply to ellenbrys Cancel reply